The internet is abuzz with anecdotes telling of the amazing benefits of a ketogenic (or “keto”) diet. Nothing new there, then, as every year is marked by the rise and fall of a new diet fad – most amplified by the social media echo-chamber but with little to commend them.

This time, though, it caught my attention. Not just because I am a modestly overweight 52 year old whose love for food and drink is slightly stronger than my desire to be skinny, and as a result someone who has been on a diet every January for at least 20 years and now knows he needs he miracle. But because of the science behind it.

Visit DIY carport plans

For a start, I first began reading about ketogenic diets thanks to Ethan Weiss, M.D., a prominent UCSF cardiologist on Twitter, whose scientific acumen I respect. If he believes in the benefits of ketosis, then I should definitely look a little closer. After 20 years of January diets, my own experience suggested that nothing made any difference: you only lost weight if you took in less calories than you used, and if you took in less calories than you used then you were hungry. Simple as that. Could it be that a ketogenic diet really was different?

Well, the principle makes sense. Bizarrely named “ketone bodies” are actually molecules that act as the body’s natural back-up fuel supply when glucose is scarce. Normally, we only enter ketosis (where ketone bodies accumulate in the blood) when we starve ourselves – not just overnight or by missing a meal, but for several days at time. Our metabolism then switches to fat-burning, and converts stored fat molecules into ketone bodies that can power our muscles and brain because the glucose has run out. Being in ketosis, then, does sound like a great way to burn off the fat. On the other hand, not eating for days doesn’t sound much fun.

But it turns out you don’t need to starve yourself to get into ketosis. All you need to do is remove carbohydrate from the diet (not just refined carbs, such as sucrose or high fructose corn syrup, but all carbs, including complex carbs and starches too). Once the body has no source of glucose, it has to switch to ketosis because the brain needs either glucose or ketone bodies to survive. So no matter how much protein or fat you eat, the body still has to break down fat to ketone bodies to keep you going.

A ketogenic diet, then, is any diet that switches your metabolism to ketosis. And the ones doing the rounds at the moment aren’t the first or the only diets to do that. It is several decades since the Atkins Diet rose to prominence – and I witnessed first-hand the weight loss some friends achieved on Atkins. The Atkins diet is a ketogenic diet, because it removes carbs from the diet and replaces them with protein. The surprising finding was that Atkins followers discovered they were much less hungry than they expected, suggesting that calories from protein made you feel more satisfied for longer. Feeling fuller translates to willingly eating less, and in the end impressive weight loss.

In dieting, though, there is no such thing as a free lunch (or so I thought). Adherence to the Atkins diet has side-effects, and most worrying is the impact on nitrogen balance from taking in so much protein. There is a very real risk of dehydration, and over the longer term, kidney stones from the need to excrete so much excess nitrogen as urea.

So what about the 21st century version? Keto today replaces the carbs with fats rather than protein. A typical Atkins regimen had 75% of calories from protein, 25% from fat and <5% from carbs. By contrast, today’s keto diets advocate 75% of calories from fat, 25% from protein and <5% from carbs. As protein intake isn’t changed from a typical “balanced” diet, any side-effects from nitrogen imbalance are neatly side-stepped.

But what about all that fat? Surely that’s got to be unhealthy? Well, no. Most instructive are the lipid profiles of Antarctic explorers who have crossed the continent on foot, dragging their own food on sledges. That’s only possible with food that has the highest possible calorie to weight ratio – which means eating essentially nothing but butter. And after months on an all-butter diet the level of LDL-cholesterol (often called “bad cholesterol”) actually declines significantly. That isn’t as surprising as it sounds – while in ketosis, fats are being moved from stores towards the liver (where the ketone bodies are made) and that’s the job of HDL-cholesterol. LDL-cholesterol typically moves excess fat from the liver to the stores in the rest of the body (hence in the opposite direction). So in ketosis, you would expect a lipid profile normally considered healthier (higher HDL and lower LDL) no matter how much fat was being consumed.

But if the benefits of Atkins on weight came from the reduced hunger thanks to the sustaining properties of protein, then you shouldn’t get that unless you bulk up the protein component of the diet. It turns out, though, that the reduced hunger results from the state of ketosis itself. How you achieve it doesn’t really matter.

So the science stacks up – theoretically, at least, I couldn’t find a flaw in the modern ketogenic diet. So I gave it a try in place of my usual “low-everything” calorie restricted January diet.

On 1st January, I weighed in at a portly 196lbs, which on my 5’9” frame amounts to a BMI between 29 and 30 (so only a smidgeon under “obese”). The “Deliciously Keto Cookbook” by Molly Pearl & Kelly Roehl duly arrived from Amazon, and my carb intake immediately fell below 5%. As I sat eating rib-eye steak for breakfast, topped with chili-butter, along with scrambled eggs and cheese, it was hard to believe I was on any kind of diet. If, like me, you think food needs to have fat in to taste good then you are going to find keto one easy regimen to follow.

I typically work-out every day for 30minutes, on a Concept 2 indoor rowing machine, and to help the diet along, I increased that to 45minutes, allowing me to row 10km (without leaving the comfort of the gym). That exercise probably helped rid my body of stored carbohydrate (your liver stores quite a lot of carbohydrate as glycogen, ready for quick release to power your muscles) quicker than normal, and within 48 hours I had achieved Nirvana (well, ketosis anyway). Using urine dipsticks, my ketone body level was sustained above 6 mmoles/litre, equivalent to a “deep” ketosis.

And there it has stayed for a month, while I enjoyed the delights of burgers topped with brie, jumbo prawn salads with avocado and sour cream dressings and creamy pork stroganoff with zucchini ribbons. Three fat-laden meals every single day.

First the benefits: once ketosis was well-established three days in, I found I was never hungry. I had no desire whatsoever to snack between meals (usually a big weakness), and gradually over a month I found myself thinking less and less about food – to the point missing lunch altogether was something that could happen “by accident”.

I also found my concentration and focus dramatically improving. I had never had so much energy, and productivity went through the roof. Running on the back-up batteries (the ketone bodies) is so much better than fuelling yourself with carbs. Why was that? Quite simply because the levels never decline (at least for a chubby person like me, with a boundless supply of internal fat stores to burn). By contrast, when you eat carbs, the excess is immediately squirreled away as fat (for a rainy day) so that blood glucose levels fall a few hours after eating and that triggers the urge to eat again, but also a feeling of declining energy and concentration (that “late afternoon dip” us ‘carbavores’ recognise only too well).

And eating less did indeed translate into impressive weight loss (14lbs gone in under a month), mostly from the unsightly and unhealthy abdominal fat deposits, so my waistline shrunk two notches on my belt too. That’s about twice as much weight-loss as my usual miserable January diet can achieve by making me constantly hungry.

There were even some unexpected benefits I noticed. For example, the amount of plaque on my teeth reduced to almost zero (presumably because the plaque bacteria need the dietary carbs to feed off).

To be honest, I feel like a teenager again.

What about the downsides? Aside from annoying my friends with constant tales of the benefits of a ketogenic diet (the newly converted are always the noisiest proselytizers), there were only two downsides I could think of.

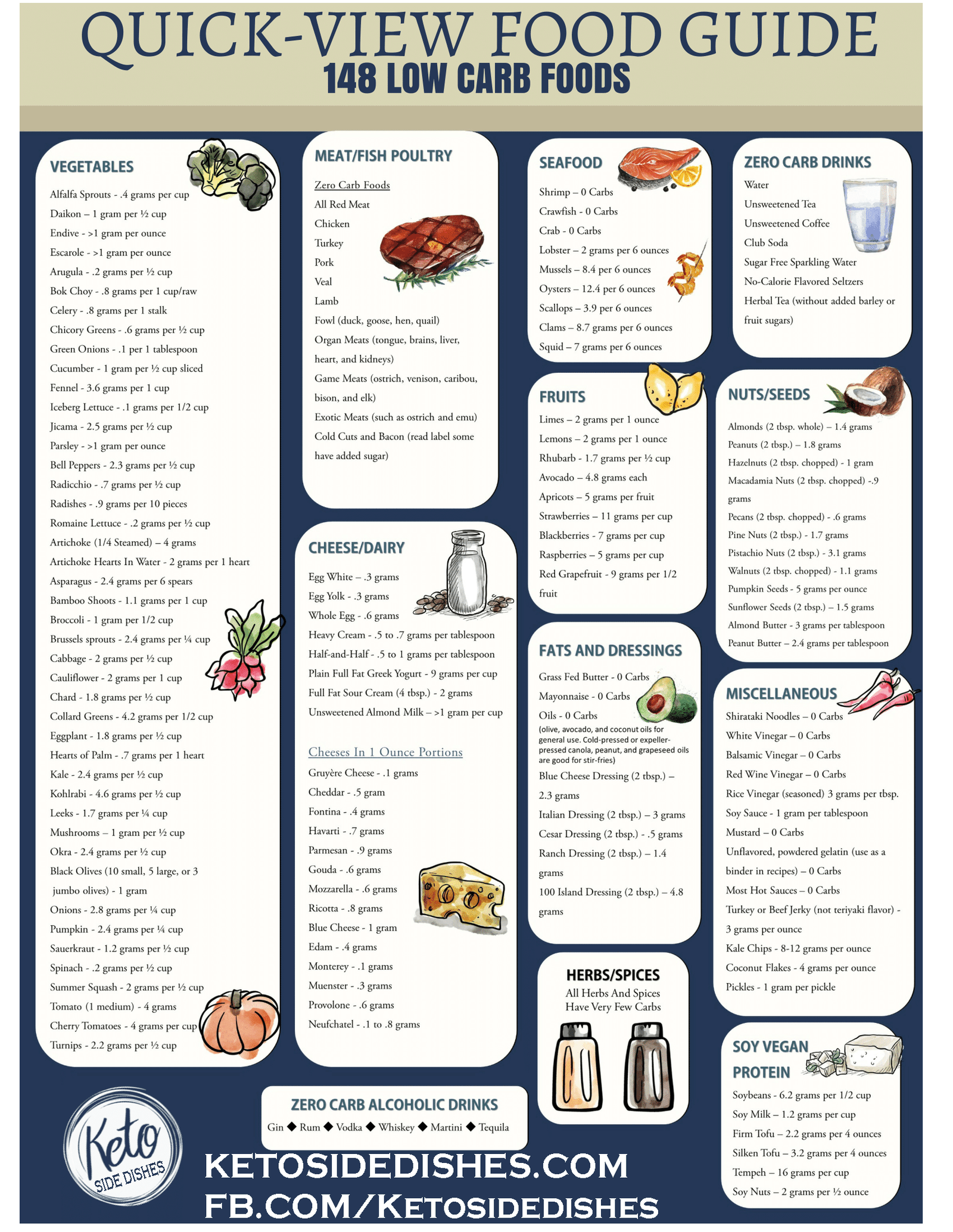

The first is simply practical. Keeping carbs below 5% of total calories is a challenge. You have to check the carbohydrate content of everything that you eat, and you find sneaky carbs hiding in almost everything pre-prepared. Eating out at restaurants becomes a challenge, and as a guest with friends and family almost impossible (unless they are also on a ketogenic diet or are incredibly accommodating). As a result, planning and preparing food becomes a significantly greater demand on your time and resources than it was before.

On the same lines, you do have to exert accurate portion control too – as the meals, high in fat, have a high calorie density, you can unintentionally eat too many calories. And even the keto diet can’t break the physical laws of the universe such as the conservation of energy – to lose weight you have to eat less calories than you need. It just means you feel great while doing it.

The second downside was simpler to avoid – but I had been slow to heed the warnings I had been given. It is hard to get enough fibre while following a ketogenic diet, principally because most natural fibre sources also contain too much available carbohydrate (fibre is typically an insoluble or indigestible carbohydrate polymer, so its unsurprising it naturally co-exists with digestible carbs). The solution is simple: take a fibre supplement – for me, I need 7 or 8 grams a day – from the first day you switch to a ketogenic diet.

At the end of my experiment, I decided to observe the impact of eating some carbohydrate after almost a month being essentially carb-free. Just 50g of carbs in one sitting (equivalent to a very small baked potato) immediately killed ketosis. Within 3 hours, urinary ketone body levels had fallen to essentially undetectable – hunger returned and the “mental fog” started to descend.

Of course, it then took almost 72 hours to re-establish “deep” ketosis after just one (in my case deliberate) moment of weakness. Three days of feeling a bit rubbish, lacking in energy, because I was denying my body its usual glucose fuel and the back-up batteries, the ketone bodies, were yet to cut in. Success on a ketogenic diet, therefore, clearly requires the kind of discipline typically associated with a Zen master.

This experiment illustrates very nicely the problem a “balanced” diet causes for the metabolism of a modern human. Ketosis is slow to establish but very quick to turn off – a phenomenon scientists call hysteresis. And there are very good evolutionary reasons for this set up: while a good fuel, glucose and other carbohydrates can damage the proteins that make up your cells and tissues. If glucose levels are allowed to get too high, the damage may be irreparable (as can happen in diabetes). To avoid that, at least in healthy people, the body makes insulin as soon as blood glucose levels start to rise – and insulin caps the level of glucose in the blood by instructing the liver to convert the excess into fat. At the same time, however, that insulin turns of ketosis (which is why ketosis ended so quickly after I ate a baked potato). That ensures you are not laying down fat and burning fat at the same time (which would be a highly inefficient use of food resources).

In prehistory, evolution tuned our metabolism so we didn’t immediately start tucking in to our fat stores the moment food became scare. Individuals who did that would find that when a potentially catastrophic food shortage occurred they would have less fat stored and so be the first to succumb. Of course, today, when for most people in developed countries, availability of calories is unlimited this hysteresis that once made us efficient now makes us fat. Every ounce of excess carbohydrate is stored away as fat, but those stores are not re-accessed as soon as your glucose is depleted. Instead you are left feeling hungry and lacking in energy for a while – and with fast-food fries within easy reach it’s just too tempting to re-fuel with carbs again.

Ketosis was, once upon a time, key to giving humans a survival advantage. The science, and my personal experience, suggests it can indeed do the same for individuals today. If you havent tried it yet, maybe you should.

Source : https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidgrainger/2019/02/01/the-science-behind-ketogenic-diets-or-why-we-get-fat-and-what-to-do-about-it/